The Dalai Lama has named a US-born Mongolian boy as the tenth Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa, the head of the Janang tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and the Buddhist spiritual head of Mongolia, a report by the Times said.

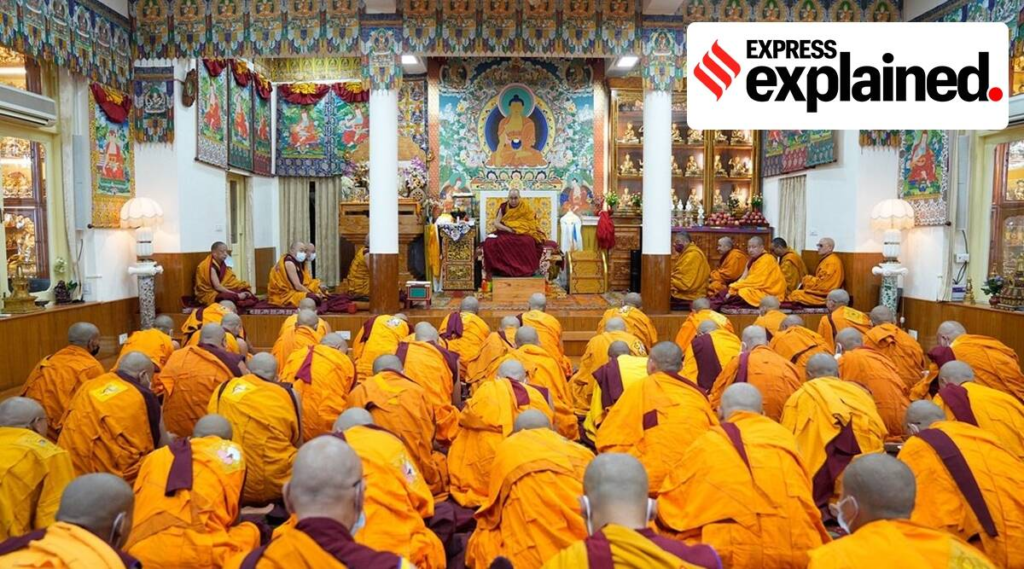

“We have the reincarnation of Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa Rinpoche of Mongolia with us today,” he told the 600-odd followers at the unveiling ceremony, understood to have taken place on March 8 in Dharamshala, the Times reported.

The ninth Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa died in 2012 at Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Since then, there had been a tense wait for his reincarnation. In 2016, during the Dalai Lama’s latest visit to Mongolia, he announced that the Jetsun Dhampa had been born in the country and the search was on to find him.

The boy unveiled, reportedly a scion of one of Ulaanbaatar’s most prominent business and political families, was deemed to be the said reincarnation. He is reportedly one of the twins born to Altannar Chinchuluun, a professor of mathematics at the National University of Mongolia, and Monkhnasan Narmandakh, a chief executive at a business conglomerate.

The latest announcement has brought attention back to the larger question of the 14th Dalai Lama’s own reincarnation. The Dalai Lama is the foremost spiritual and temporal authority of Tibet. Over the past 70 years of Chinese occupation, he has been Tibet’s loudest, most popular and outspoken voice, while living in exile in Dharamshala, India. This makes the issue of his reincarnation one with deep ramifications on international politics.

“The Dalai Lama’s reincarnation is a civilizational struggle between China and Tibetans over who controls Tibetan Buddhism,” Amitabh Mathur, a retired adviser to the Indian government on Tibetan affairs, told NPR in 2019.

Buddhism became the predominant religion in Tibet by the 9th century AD. It evolved from the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions of Buddhism, incorporating many tantric and shamanic practices of both post-Gupta period Buddhism in India as well as the Bon religion which was spread across Tibet before Buddhism’s arrival.

Tibetan Buddhism has four major schools: Nyingma (8th century), Kagyu (11th century), Sakya (1073), and Gelug (1409). The Janang school (12th century) is one of the smaller schools that grew as an offshoot of the Sakya school. Since 1640, the Gelug school has been the predominant school of Tibetan Buddhism. The Dalai Lama belongs to this school.

The cycle of birth, death and rebirth is one of Buddhism’s key beliefs. “As long as you are a Buddhist, it is necessary to accept past and future rebirth”, the Dalai Lama said in a 2011 sermon on the subject (translated from Tibetan).

However, early Buddhism did not organise itself based on this belief in reincarnation. In fact, early Buddhist ‘orders’ were scarcely ordered at all – with next to no hierarchy and little organisation. “It was merely a brotherhood of monks”, LA Waddell wrote in his authoritative The Buddhism of Tibet or Lamaism (1895).

Tibet’s hierarchical system seemingly emerged in the 13th century. It was also around this time that the first instances of “formally recognizing the reincarnations of lamas” can be found. The Dalai Lama traces this tradition to “the recognition of Karmapa Pagshi as the reincarnation of Karmapa Dusum Khyenpa by his disciples in accordance with his prediction”. Since then, this custom slowly spread to all Tibetan traditions.

Notably, in 1417, Jé Tsongkhapa founded the Gelug school, which developed a strong hierarchy and by 1640 it leapt into the temporal government of Tibet with the assistance of Mongol prince Gusri Khan. The fifth grand lama of the school, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso, was conferred the title of Dalai Lama (‘Dalai’ being the Mongol word for ‘ocean’). To consolidate his rule, he instituted the tradition of succession through reincarnation in the Gelug school, himself claiming to be the reincarnation of Avalokiteshvara, one of the most important Bodhisattvas in Mahayana traditions.

Since then, “a series of unmistaken reincarnations has been recognised in the lineage of the Dalai Lama”, the Dalai Lama said in 2011. According to Tibetan Buddhist tradition, the spirit of a deceased lama is reborn in a child. “This secures a continuous line of succession through successive re-embodiments”, John Powers wrote in his book Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism (1995).

Several procedures are followed to recognise Tulkus (recognised reincarnations).

The predecessor himself leaves guidance regarding his reincarnation. The prospective child then has to undergo multiple ‘tests’ in which they ‘recall’ their past lives and recognise objects that their predecessor used, such as spectacles, prayer beads, etc. Other oracles and lamas with the power of divination are also consulted before the final proclamation is made.

There are also procedures to iron out disputes. “When there happens to be more than one prospective candidate for recognition as a Tulku … there is a practice of making the final decision by divination employing the dough-ball method (zen tak) before a sacred image while calling upon the power of truth”, the Dalai Lama said in 2011.

This system of succession by reincarnation works at various levels of the Buddhist hierarchy.

The Chinese occupation of Tibet and the Dalai Lama’s exile has raised significant complications in the established traditions of reincarnations in Tibetan Buddhism.

While China’s initial attempts to establish its authority in Tibet employed direct, repressive tactics (especially during Mao’s Cultural Revolution when thousands of Tibetan monasteries and cultural sites were destroyed), of late, China’s policy has focussed on controlling Tibetan Buddhism itself in order to “pacify the highly devout Tibetan public”.

Not that China is not repressive anymore. Monasteries are highly surveilled, schools do not teach Tibetan language, culture and history, and dissenting voices often just ‘disappear’. But China has also ‘invested’ millions of dollars to rebuild and renovate many monasteries and recognised Buddhism as an “ancient Chinese religion”.

The succession of the Dalai Lama is of utmost importance in this project. For years, the Chinese government has attempted to discredit the Dalai Lama, calling him a “wolf in monk’s robes”, claiming that he forfeited his authority over Tibetans 60 years ago, when he went into exile. However, the Dalai Lama still remains venerated in Tibet, even though the Chinese government has systematically attempted to remove him from public consciousness, including by banning his portrait across China. By controlling his succession, the Chinese seek to, once and for all, take control over Tibetan Buddhism and consequently, Tibetan Buddhists.

According to the ‘State Religious Affairs Bureau Order No. 5’, passed by the Chinese government in 2007, “a reincarnation application must be filed by all Buddhist temples in that country before they are allowed to recognise individuals as tulkus”.

On his part, the Dalai Lama has outrightly rejected any authority the Chinese claim to have regarding his and other other lamas’ reincarnation. “The person who reincarnates has sole legitimate authority over where and how he or she takes rebirth and how that reincarnation is to be recognised,” declared the Dalai Lama. He adds, “It is particularly inappropriate for Chinese communists … to meddle in the system of reincarnation and especially the reincarnations of the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas.”

But, while the Dalai Lama, currently 87, claims he will live till the ripe age of 113 and have enough time to decide upon his reincarnation, his old age and shaky health concern many Tibetans. “If His Holiness leaves this world without certainty about what comes next, there will be trouble”, a devotee told NPR.

The potential for confusion is aggravated by the fact that the Panchen Lama – traditionally the second most important figure in the Gelug tradition, responsible for naming and grooming the next Dalai Lama – chosen by the 14th Dalai Lama remains ‘missing’ since he was kidnapped by Chinese authorities in 1995. Gedhun Choekyi Nyima was only 6 at the time of his abduction and has never been seen since.

Chinese authorities selected their own Panchen Lama, a six-year-old boy named Gyaincain Norbu, in 1995. Today, he is the vice-president of the Buddhist Association of China and seen in monasteries across Tibet, spreading pro-China messages.

The question of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation is set to linger on for the foreseeable future. The Dalai Lama himself has not provided a definitive answer regarding what will happen. At different times, he has dodged the question with his disarming smile, claimed that there is ample time to make the decision, and even suggested that there may be no Dalai Lama after him.

In 2011, announcing his retirement from worldly affairs, the Dalai Lama handed over his temporal authority to an elected Tibetan government-in-exile, the Central Tibetan Administration. “The rule by kings and religious figures is outdated”, he said. The CTA runs as like any modern government with various ministries and a constitution.

However, given the symbolic authority that the Dalai Lama due to his importance to millions of Tibetans across the world and through the sheer strength of his charisma, the question of his reincarnation continues to hold great political implications.

Binge-watching on YouTube? These 5 tips can enhance your viewing experience

Arjun Sengupta… read more