The Financial Express

By Pradeep S Mehta & Amit Dasgupta

We live in troubling times.

A series of recent developments suggests that we have rapidly gravitated towards a deeply divided world teetering on the brink of calamitous confrontation. History is repeating itself. Simultaneously, multilateralism will suffer and thus crucial problems like climate change and indebtedness will not receive the international community’s deserved attention.

Almost half of the 20th century was characterised by the Cold War that not only triggered an arms race but also divided nations based on us-versus-them. Animosities were so deep that even after the disintegration of the former Soviet Union, suspicion and enmity has defined the relationship with Russia for several countries, especially with the US.

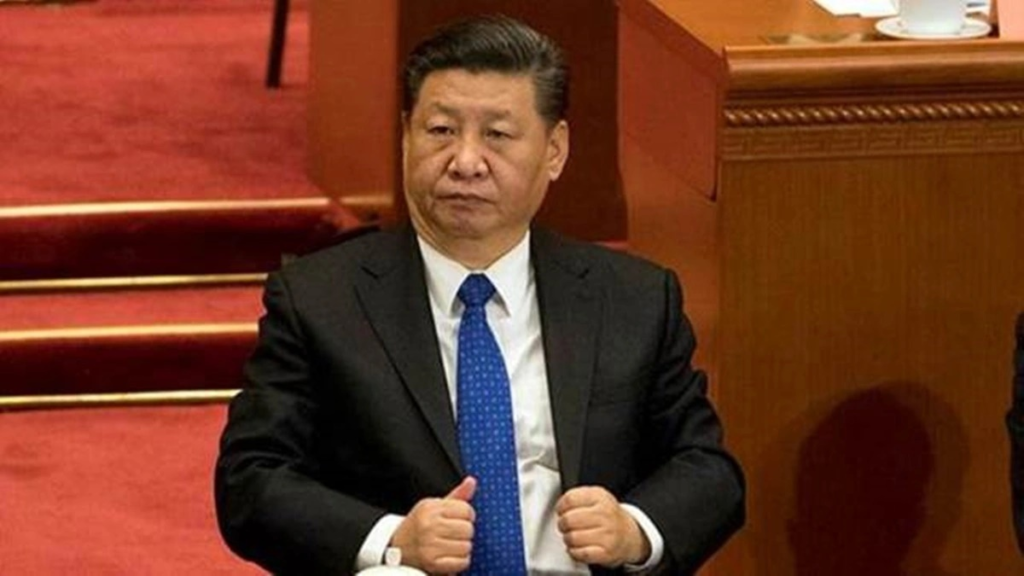

Today, Beijing’s aggressive and hegemonic behaviour, especially accentuated during Xi’s tenure, is the new baddie. It has driven countries to seek out defence and military partnerships as a deterrent to anticipated Chinese adventurism and territorial expansionism. Recent events are a testimony to this volatile situation. Indeed, it might well be argued that the stage is set for a Cold War in the Indo-Pacific.

Consider developments over the past few weeks, for instance. Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese visited India and while a slew of bilateral agreements was signed, signifying deepening relations, he did not shy away from identifying the Chinese threat in the Indo Pacific as a key concern that united both countries. Consequently, the agreement to intensify joint military exercises and enhanced defence dialogue and cooperation was an inevitable outcome.

A few days later, Japanese prime minister Fumio Kishida visited India. Apart from extending an invitation to prime minister Modi to attend the G7 Summit in Japan, he announced an Indo Pacific development assistance initiative aimed at countering Beijing’s growing influence in the region. It may, furthermore, be recalled that in December last year, Japan made changes in its security policy enabling it to deploy long range cruise missiles to strengthen its strike back capability in the event of a Chinese attack.

Meanwhile, as part of AUKUS, a massive tripartite deal was struck whereby Australia would acquire eight nuclear-powered submarines over the next thirty years at an estimated cost of $368 billion. In a significant move, from this year itself, Australian military and civilian personnel will embed with US and UK navies. It was also agreed that UK submarine design and US defence technology would join together to create the future attack submarine SSN-Aukus that both the UK and Australia would deploy. None of this would happen overnight but signal a dramatic development in response to increased Chinese assertiveness in the Indo Pacific. It may be recalled that China had been agitated with the creation of AUKUS and its stated objective of providing nuclear submarines to Australia, as an unambiguous affront to China.

Recognising that it was being encircled, Xi dashed off to meet president Putin and was greeted with predictable fanfare. Both leaders spoke of ‘a new era of friendship’ between Moscow and Beijing. What this means in precise terms is a matter of speculation. Given Russia’s preoccupation with Ukraine, it certainly would not translate into any kind of military or defence support.

But more is yet to come. It is likely that the Quad Summit, to held in Sydney in May, would make the Indo Pacific a key concern when the US president, and the prime ministers of Australia, India and Japan meet. Unlike AUKUS, which is openly a defence and military grouping, the Quad has, so far, avoided overt defence discussions. It may, however, be recalled that since 2021, leaders of the four countries have seen strategic convergence in their perspective over China and its hegemonic ambitions that threatens global welfare. Exercise Malabar in the Indo Pacific that will follow in a couple of months of the Quad Summit, bringing the navies of these countries together in joint naval exercises, would be further reiteration of this shared concern and in fact, shared strategic messaging to Beijing.

Xi’s response would reflect how history would unfold. For the present situation, he has only his wayward adventurism and autocratic style to blame. His international image as a recalcitrant bully, who buys rather than make friends, and then leaves them in deep debt does him no credit. Sri Lanka and African nations are a clear example of the dragon’s embrace. Then, there’s the Galwan Valley misadventure underestimating India’s preparedness and fightback.

To understand how Xi would respond, it is important to understand how Asians think. ‘Face’ is an important part of cultural narrative among Asians. In the Chinese language, the word is miansi and reflects the importance of respect. Disrespect or losing face is looked down upon and would, certainly, attract retaliation. Xi cannot, consequently, afford to back down, as he would lose the respect of the Chinese people and thus, control of the party. It could even trigger a coup.

It would be logical to assume, therefore, that Xi would become hardline in his approach, undeterred by the developments aimed at contesting, what he considers to be, Beijing’s national and security interests.

We live, as the Chinese would say, in interesting times. It is, certainly, not likely to be comfortable in the future.

(Pradeep S Mehta & Amit Dasgupta, respectively, secretary-general, CUTS International, and distinguished fellow, CUTS International & Australia India Institute)

Get live Share Market updates and latest India News and business news on Financial Express. Download Financial Express App for latest business news.