By Emil Avdaliani

Russia and Iran are advancing the idea of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a transportation route which despite some problems, is progressing and could reshape Eurasian connectivity.

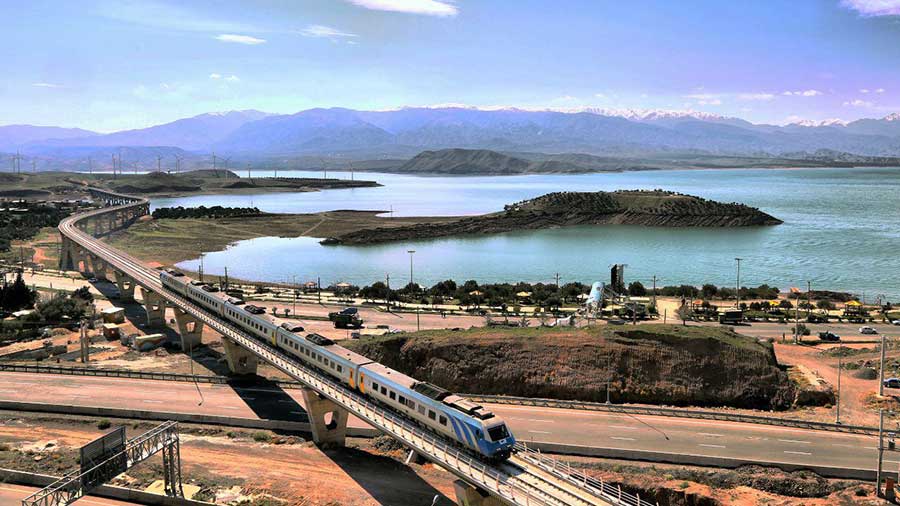

Conceived in early 2000s by Russia, India, and Iran, when an intergovernmental agreement was signed to create a multimodal transport corridor, the 7 200 km-long-project from India and Iran to Russia has seen little meaningful progress. Russia mostly served as a transit for east-west connectivity, while trade with Iran, largely flowing through both sides of the Caspian Sea either via Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan or Azerbaijan, was lagging behind Iranian and Russian expectations. A critical link between Russia and Iran is Azerbaijan where the remaining railway connection remains incomplete. The Rasht-Astara railway section (right on the border between Azerbaijan and Iran) requires millions of dollars in funding. Russian contractors have been mooted as completing this link, with payment by Iran to be made in oil, and Azerbaijan has recently been more cooperative, but as of now, the route remains unfinished.

Nonetheless, the advantages of the INSTC are obvious. First there is a significant reduction in the delivery time of goods from India to Europe.

The INSTC can also connect the Persian Gulf and Indian ports with Russia, a dream that fired the Russian imagination during its 19th century imperial expansion and has taken on added impetus given the massively increased volumes of Indian purchases of Russian oil and gas. Access to warm water ports works for both Russia and India and provides an alternative to lengthy sea routes for trade to Russia, Turkey, and the rest of Europe. Ideally, the route would take 18 days from the Baltic Sea to reach India through Azerbaijan and Iran. Compared to the Suez Canal route, goods can be delivered via the INSTC twice as fast.

The corridor consists of several branches. The Trans-Caspian direction is through the Caspian Sea. The Western “branch” runs along the western coast of the Caspian, following through Russia and Azerbaijan. The Eastern route runs through the territory of Iran, entering the territory of Turkmenistan and then goes through the territory of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. At the same time, this route may not affect Uzbekistan, but go directly through Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan – along the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea. As a result, the corridor has every chance of becoming one of the main arteries for connecting Europe and Asia.

It is, however, the Western branch which is the most important due to the fact that Russia’s and Iran’s most populous provinces are located exactly in western areas of the countries and less so in eastern parts which border on Central Asia from the north and south. This makes the lack of the 164-kilometer Rasht-Astara rail route ever more problematic in the rapidly expanding economic relations between the two countries.

The most important driver behind the implementation of INSTC is the Ukraine conflict, and how as a result of the Western sanctions imposed on Russia, Moscow attempts to find alternative routes to global markets, such as the Gulf States, East Africa, India, and South Asia.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Iran in July 2022 brought about a flurry of comments on the need to complete the corridor, perhaps a sign Russia now, as opposed to the pre-2022 period realizes just how important the project is. Previously, the Kremlin had been somewhat ambivalent. To be sure, it supported the idea from the very beginning, but has never really seriously pushed for its quick implementation. But with the consequences of the Ukraine situation, there is a considerable incentive to revive the flagging scheme, which could help the two Eurasian powers, increase trade and build momentum against Western sanctions.

The fresh impetus has been clear from official comments and practical moves from 2022 onwards. The director of the Iranian Construction and Development of Transportation Infrastructure Company, Abbas Khatibi, said in the wake of Putin’s visit that the country is willing to complete the project. On June 11, two containers set off from St. Petersburg to Astrakhan, then to the Iranian port of Anzali on the Caspian Sea, and ultimately to Bandar Abbas on the Persian Gulf. The freight transit was a test, but the timing was telling, as it coincided with Putin’s visit to Iran. This followed the Iranian Roads and Urban Development Minister Rostam Qasemi’s trip to Moscow in April where a comprehensive agreement on transportation cooperation was signed with the Russians. Later in September Iran, Russia and Azerbaijan signed a special declaration on the INSTC that saw the two countries underlying the importance of the transportation corridor.

On August 22, 2022, the heads of the customs authorities of Azerbaijan, Iran and Russia signed a memorandum on the facilitation of transit traffic. Later in October that year the Head of Iran Railways said that earlier that month seven Russian freight trains had reached India through Central Asia via Iranian territory. Similar developments took place In July when a Russian train consisting of 39 containers traveled some 3,800 kilometers through Central Asia to enter Iran.

As a further reflection of Russian interest in the implementation of the project. Russian presidential aide and State Council Secretary Igor Levitin visited this rail route this January. The visit was an important milestone as the agreement between two countries was reached whereby the rail project will be completed within three years mostly with Russian investment for the 152-kilometer railway line, while the Iranian side will be financing the 12 km section.

Nevertheless, the talks are moving slowly as US sanctions still hamper the initiative. The Iranian side however remains hopeful to see the completion and launch of the North-South transport corridor by 2025, Economy and Finance Minister Ehsan Khandouzi said in an interview with Russia-state media RIA Novosti.

For Iran, the corridor opens access to the 10 Russian cities of 1 million consumers or more along the River Volga, but also as a connection to wider Central Asia and the Black Sea region. From Azerbaijan, Iranian goods could head eastward to Kazakhstan’s Aqtau port. Yet another possibility is to look westward toward Georgia’s Black Sea ports and the European market. This latter possibility will be more realistic when US lifts its sanctions.

The expansion of the corridor is nevertheless obvious. For instance, cargo transportation by Russian Railways via the corridor doubled in February 2023 compared to the same month of the previous year and reached 764,000 tons. In total, in January-March period the cargo shipments exceeded 2.3 million tons, out of which 2.2 million tons have been shipped via the Western branch and 74,2 thousand tons via the Trans-Caspian route. The rest was processed through the Eastern – Central Asian route. This means that the transit through the corridor’s branches experienced exponential growth: the Western line with a 2-fold increase, the Transcaspian route 3-fold, and the Eastern route to China an astonishing multiple of 33 times.

However, seen from a much wider perspective, even if a milestone of 10 million tons per year is achieved by the 2023 year end, this will still be much less than, for example, Russian Railways are processing – a staggering 3,5 million tons per day. The expectation in Iran is that it can handle up to 20-25 million tons per year through the INSTC. The Russian side expects that the transit will increase current 17 million tons to 32 million tons by 2030.

The expansion of the INSTC fits into the overall growth of Russian-Iranian trade relations. Here again, the Ukraine conflict, and Russia’s resulting redirection of its trade toward its Eurasian partners serves as a major incentive. By the end of 2022, mutual trade between Russia and Iran reached record levels of US$4.9 billion, exceeding the figures for 2021 by more than 20%. Bilateral trade is based on foodstuffs and agricultural raw materials. In the case of Russian deliveries to Iran, cereals and vegetable oils are key items.

The boost to bilateral trade through the INSTC could be made with yet another potential development. Since 2019, an interim agreement on a free trade zone has been in force between Iran and the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). It was supposed to expire in October last year, but the agreement was extended by a special protocol until 2025 or until the entry into force of a new agreement on a permanent free trade regime, negotiations of which are currently being finalized. The signing of such an agreement with Iran is important not only in terms of reducing customs duties. Iran is not a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and therefore Iranian business is not focused on international standards of trade regulation in such areas traditional for the WTO as the use of quantitative restrictions, market protection measures.

Despite the overall positive thrust from Iran and Russia, serious problems nevertheless persist for the INSTC. Firstly, Iran aims at achieving US$20 billion in 2023 from its increased role as a transcontinental transit country. Yet the problem is that the infrastructure which remains hampered by US sanctions, Iran’s current transit potential is less than 10 million tons – a significant discrepancy with a potential shortfall of 200 million tons per year. There is also a major shortage of transit wagons and relatively poor road infrastructure which makes it difficult to sustain higher levels of traffic. The railway infrastructure is likewise poorly developed due to geographic constrains and the lack of investment. As a result, around 90% of the country-wide transit is carried out through the road system putting additional stress on its capacity.

There are other practical problems such as the lagging construction of 22 tunnels and the construction of 15 special bridges along the corridor in Iran. At the same time, there is no single railway gauge option adopted for the route. The Russian standard of gauge of railways is 152 cm, in Iran – 143.5 cm. Obviously, this would make the operation of the INSTC less smooth.

Russia and Iran face other significant constrains too. First, is the financial situation. Both countries remain heavily sanctioned. While the Ukraine conflict continues and Iran’s nuclear negotiations remain stymied, Western restrictions are likely to remain in place. In normal times Russia is arguably the only power which would be able to finance the remaining Rasht-Astara railway section. With the sanctions the prospects seem less promising.

There are also recurrent tensions between Iran and Azerbaijan. Uncomfortable with an emboldened Azerbaijan and weakened Armenia, Iran might be genuinely interested in the development of the INSTC, but it hardly wants to see this route as the only option.

Less dependence on transit through Azerbaijan could only be achieved with development of alternative routes such as the one through Armenia. In November 2022 the Iranian Transport and Urban Development Minister, Rostam Qasemi met with his Armenian counterparts to discuss transit routes from Armenia to Iran to the Gulf States via Iran.

Following up on this offer, in early March 2023 Armenia proposed a Persian Gulf-Black Sea corridor to connect India with Russia and Europe. Interestingly, the offer came at a time when Armenia’s foreign minister Ararat Mirzoyan was also visiting India.

Tensions are also persistent in Azerbaijan-Russia relations. Amid the Ukraine conflict and Azerbaijan’s increasingly coercive position toward Armenia, Baku’s push to have Russian peacekeeping forces withdrawn from Nagorno-Karabakh by 2025 becomes ever more evident. Russians are understandably weary but have few tools to influence Azerbaijan’s behavior. This produces additional tensions, which trickle down in every aspect of relations between Moscow and Baku.

To this should be added yet another major constraint. Iran and Russia harbor deep-seated distrust. The two are praising their cooperation, which is propelled by animosity towards the Western, liberal order. Yet amid the growing alignment, uncertainties persist as Iranians are suspicious about Russia’s strategic goals and interests in the South Caucasus and the Middle East. Even on such issues as the provision of Iranian military drones to Russia, Iranian politicians appears deeply divided. Historically seen as an Imperial power which kept Iran’s power at bay for centuries, ordinary Iranians’ view on Russia has often passive – negative and especially so since the Ukraine conflict and Iran’s own internal pressures.

All this calls into question the short-term future of the INSTC. Significant diplomatic, financial and infrastructure barriers need to be overcome at a time when two of the major investors, Russia and Iran face serious internal and external problems of their own. The West may also wish to prevent, or at least delay the INSTC route as long as possible by fermenting regional and domestic unrest. While the INSTC may become operational in time, those looking for it to provide Suez alternatives may have to be rather more patient.

Emil Avdaliani is a Eurasian strategic analyst. He can be contacted at emilavdaliani@yahoo.com.

Previous Article

« Georgia, Uzbekistan, Prioritize the BTK Railway To Boost Trade

Next Article

Dezan Shira & Associates helps businesses establish, maintain, and grow their operations.

Stay Ahead of the curve in Emerging Asia. Our subscription service offers regular regulatory updates,

including the most recent legal, tax and accounting changes that affect your business.